The Treaty of Haddington signed at the abbey on 7 July 1548, betrothing Mary, Queen of Scots to the French Dauphin, is one of the most significant treaties in Scottish history.

There is a link to a BBC bitesize video giving context to the betrothal when you click here

The End to the Rough Wooing: The Treaty of Haddington 1548

While 2018 celebrated the 700th anniversary of Haddington being granted the royal charter by Robert the Bruce in 1318, it also marked the 470th anniversary of the Treaty of Haddington signed in 1548. Though chiefly remembered for betrothing Mary, Queen of Scots to the Dauphin of France, this epoch-making treaty marked a pivotal period in Scottish history. By ending the war with the Auld Enemy, England, it strengthened the Auld Alliance with France, which in turn promoted the Scottish Reformation and led to the Union of the Crowns. What were the circumstances that led up to this historic treaty?

Henry V111 pushes for Scotland to break from Rome 1542:

In 1542, the Protestant king, Henry VIII, was bullying his nephew, James V, into breaking away from Catholic Rome, severing the Auld Alliance with France and handing over sovereignty of Scotland. When James refused, his uncle was furious. He sent raiding parties over the border until finally in November, the English forces defeated the Scots on the boggy lands of Solway Moss. Meanwhile, in Falkland Palace, where James V was laid low by disease and despair – both his infant sons had died in 1541 – he received news that his queen, Marie de Guise, had given birth to a bonnie princess on 8th December. According to legend he turned to the wall, uttering his famous last words about the fate of the Stewart dynasty: ‘The deil gang wi it. It will end as it began. It cam wi a lass and it’ll gang a lass’. He died on 14th December aged 30, leaving the infant Mary, Queen of Scots at six days old, one of the most desirable dynastic partners in Europe – and her most persistent suitor was the lad next door – Henry VIII’s five-year-old son Edward Tudor.

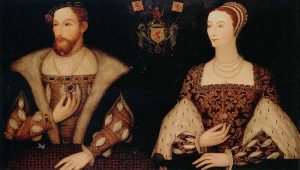

James V and Marie de Guise

Treaty of Greenwich betrothing Mary to Edward 1543:

James V’s premature death gave Henry the perfect opportunity to unite the two kingdoms without bloodshed through marriage. When ‘assured Scots’ signed the Treaty of Greenwich 1543, betrothing Mary to Edward, Henry must have thought he had finally bought off the Scots. However, he reckoned without, Marie de Guise, James’s French-born widow who was equally determined to keep the Scottish crown for her daughter and preserve the Auld Alliance. In December 1543, with the lure of French gold, she persuaded the Scottish Parliament to cock a snoot at Henry’s cunning scheme to conquer Scotland by the back door and tear up the treaty. Needless to say, this ignited Henry’s famous Tudor temper. To hammer the rebellious Scots into submission, he sent Edward Seymour (then Earl of Hertford) north with an invading army to put all to fire and sword and turn every building upside down, sparing no creature alive within the same. The trail of destruction was considerable. Edinburgh was almost totally razed, Holyrood Abbey burned down and Musselburgh and Dunbar were set ablaze. Many religious buildings were wrecked, forcing clerics to flee, never to return, thus weakening the Roman Catholic Church’s hold on Scotland. So began the first stage of the six-year Anglo-Scottish conflict that became known as the Rough Wooings, as George Gordon, Earl of Huntly, reportedly described it: ‘We liked not the manner of the wooing, and we could not stoop to being bullied into love.’

The young Queen Mary of Scots

On Henry VIII’s death in 1547, Seymour, now Duke of Somerset and Protector of King Edward VI, ratcheted up this campaign of uncourtly courtship. In September, Somerset’s troops defeated the Scots at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh, forever remembered as Black Saturday. Though victorious, the English failed to gain their prize. Immediately after the rout, the Scots spirited away the five-year-old Mary to Inchmahome Priory in Lake of Menteith for safekeeping.

Lowland Scotland under occupation by the English:

With lowland Scotland under occupation by the Auld Enemy, Mary of Guise turned for help to the Auld Alliance, dangling the carrot of her daughter’s hand for the French Dauphin, François, as a reward. Meanwhile, Regent Arran pledged that, in return for the Duchy of Châtelherault and a noble French bride for his son, he would ensure the Scottish parliament’s consent.

Treaty of Haddington 1548:

On 7th July 1548, the historic treaty was signed, not at the collegiate church of St Mary’s as is often assumed, but at the priory of St Mary the Virgin, the Cistercian nunnery, founded by Ada de Warenne, Countess of Northumberland and mother of kings – Malcolm the Maiden and William the Lion. Unfortunately, the priory (usually referred to as the abbey) was abandoned during the Reformation and now the only traces of its existence are the Abbey and Nungate Bridges and Abbey Mill. While the treaty signalled the end of the Rough Wooings, it started a lengthy siege as the French struggled to expel the English garrison.

Furious that Mary had been pinched from under their noses, the English fortified Haddington, in the hope of defeating the French and forcing them to hand her over. Not only that, Sir Thomas Palmer, in charge of the defences, told Somerset that by keeping Haddington he would win Scotland. On the other side, Henri II boasted that Haddington would not remain long in the hands of the English. After an inspection, however, D’Essé the French commander found that the burgh was much more strongly fortified than he had thought, and the siege was to become famous for being the longest in Scottish history. In the end, after eighteen months, starvation and plague forced the English to abandon Haddington in September 1549 – just as George Wishart, the Protestant martyr, had predicted.

In 1546, he had preached at St Mary’s Kirk, with John Knox standing at the foot of the pulpit bearing a two-handed sword to defend his master. To no avail. Wishart was arrested and condemned to death at the stake by Cardinal Beaton. In his final sermon, he had famously cursed the folk of Haddington for not turning out to hear the gospel.

Strangers shall possess your houses, chase you from your habitations and set upon you with sword and fire. Pestilence and famine shall afflict you. And the walls of this red-rose kirk by the Tyne will be open to the skies.

As they suffered plague, fire and famine did his prophetic words ring in their ears?

Paving the way for the Protestant Reformation and the Union of the Crowns under King James VI and I 1560:

Although Scotland emerged from the Rough Wooings with its sovereignty intact and the English repulsed, it became a protectorate of France. More crucially, the marriage treaty of 1558 contained a secret clause promising the Scottish crown to her French husband should Mary die. This treachery inflamed resentment amongst the Scots lords who formed a band of ‘patriots’, the Faithful Congregation of Christ Jesus in Scotland, to ensure political support for their religious rebellion. In 1559, they called upon John Knox, to return to Scotland from exile and lead the Protestant Reformation. However, he could not do so without the assistance of the Auld Enemy – the Protestant English. On 6th July 1560, another historic treaty was signed. The Treaty of Edinburgh overturned that of Haddington, replacing the Auld Alliance with an Anglo-Scottish agreement and the official religion of Roman Catholicism with Protestantism, which ultimately paved the way for the Union of the Crowns under King James VI and I.

Marie Macpherson

Illustrations

- Mary Queen of Scots, c. 1549, by Francis Clouet

copyright Yale University Art Gallery. In the public domain

- Marie de Guise and James V

In the public domain

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_V_and_Mary_of_Guise_02.jpg

- Prince Edward Tudor c. 1543-46 -In the public domain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_VI_of_England#/media/File:Edward_VI,_aged_6.jpg

- The marriage of Mary and François 1558 – In the public domain.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_II_of_France#/media/File:Francois_Second_Mary_Stuart.jpg

- John Knox preaching before the Lords of the Congregation – In the public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Preaching_of_Knox_before_the_Lords_of_the_Congregation.jpg

- The Fortress of Haddington from a reconstruction by Andrew Spratt

By kind permission of the artist (see attachment)

Main Sources:

Transactions of the East Lothian Antiquarian and Field Naturalists’ Society, Vol. 5

W. Forbes Gray and James H Jamieson, A Short History of Haddington, SPA Books, 1986

M. H. Merriman, The Rough Wooings: Mary Queen of Scots, 1542-1551, Tuckwell Press, 2000

Linda Porter, Crown of Thistles, Macmillan, 2013

Pamela E. Ritchie, Mary of Guise in Scotland, 1548-1560, Tuckwell Press, 2002

Rosalind K. Marshall, Mary of Guise, NMS Publishing, 1977; John Knox, Birlinn, 2000